Attending the Black Harvest Film Festival feels like a rite of passage – a celebration of Black storytelling that reflects the spirit and resiliency of our community. But as a black man, it offers something even deeper: an opportunity to escape, reflect, and find solace in shared experiences. This year’s lineup was no exception, showcasing a powerful array of films that explore identity, resilience and happiness in the face of adversity. among them, “Black Table” What ensued was a transformative viewing experience that I will not soon forget.

In light of the political unrest and sense of despair in the United States, John Antonio James and Bill Mack’s documentary “Black Table” is exactly the film I needed. It chronicles the journey of several Black Yale alumni as they unite for their 25th college reunion, reflecting on their time at the prestigious university and living together around a shared dining table, one meal at a time. Get solace from others.

“Black Table” is more than a snapshot of these students’ experiences – it resonates as a universal narrative for black people in the diaspora. It reflects the shared struggle for survival in predominantly white spaces, where being “other” and being ostracized for how you look is a very painful and isolating reality. Yet, the documentary also shows that community is the key to resilience. Through solidarity, Black people not only survive but thrive in environments that often seem inhospitable.

Unfortunately, the challenges facing black communities remain the same from generation to generation. Yet, it is also a very hopeful story. Despite the hardships these alumni faced on campus, they created happiness and kinship among themselves, symbolized by their chosen table in the dining hall. Their laughter and camaraderie were acts of quiet rebellion, and this film is a testament to the power of that resistance.

At a time when affirmative action was phased out in 2023 and DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) initiatives are being rolled back, the “Black Table” feels especially thought-provoking. It reminds us, as Kendrick Lamar rightly said, that “we’re gonna be okay.”

“Getting up at night,” Nelson Makengo’s debut feature documentary is a mesmerizing experience. The film explores the aftermath of a turbulent election and the proposed construction of Africa’s largest power plant in Congo, a project that has plunged 17 million people into darkness. From the first frame, the viewer is engulfed in shadow – not a blank, empty void, but an omnipresent darkness full of texture. It’s the kind of darkness you feel when you close your eyes, with invisible particles flickering like an unknown camera capturing hidden realities.

Makengo skillfully finds beauty in darkness, using minimal light sources – a phone, a flashlight, a headlamp – to illuminate his subjects. Yet the true brilliance of “Rising Up at Night” lies in its depiction of the people of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Makengo invites viewers into the community, offering an intimate, quietly observed perspective that feels like being a fly on the wall. The warmth and resilience of the people of Kinshasa is reflected, their smiles and deep connection with each other create an emotional connection. His unwavering faith and perseverance against insurmountable odds inspires both admiration and longing for transformative change on his part.

The film is a holistic narrative, blending the perspectives of everyday citizens like Davido, who seeks shelter after his home floods, as well as the perspectives of prominent community leaders like Pastor Gedion and Kudi . These two men carry the story, displaying strength and charisma that captivates the audience and elevates every scene they watch.

Makengo’s story is a revelation, proving that cinema can be a powerful medium to raise voices. With “Rising Up at Night,” Makengo offers a forceful voice for justice and humanity, leaving no doubt that her creative journey is destined for greatness.

Nigerian filmmaker Daniel Oriahi “weekend” It’s a thrilling ride from start to finish. The story focuses on Nikiya (Uzomaka Anyunoh), an orphan who spends a weekend with her fiancé’s estranged parents for their wedding anniversary. However, this happy occasion is surrounded by a dark family tradition that makes the film scary. Oriahi skillfully builds tension in the early moments, creating a palpable unease that lasts until the first murder. It keeps the audience on the edge of their seats, the suspense increasing with every turn.

Bucci Franklin is a standout as Luke, bringing a desperation to the character that intensifies with each scene, leaving the audience to question what “doing the right thing” might look like in such a family. Aniunoh’s portrayal of Nicaea is also notable; She serves as the audience’s eyes and ears and uncovers Luke’s family’s disturbing secrets. Like Nikiya, we are unaware of the family’s hidden truth until it is slowly and terrifyingly revealed.

While “The Weeknd” has its roots in horror, it is also a tragic love story. Luke and Nikia seem very different from each other, with Nikia yearning for family ties while Luke is desperately trying to move away from her. Tragedy and trauma converge in an unexpected ending, underscoring that love sometimes falls short. If Hollywood isn’t calling Oriahi yet, it needs to be.

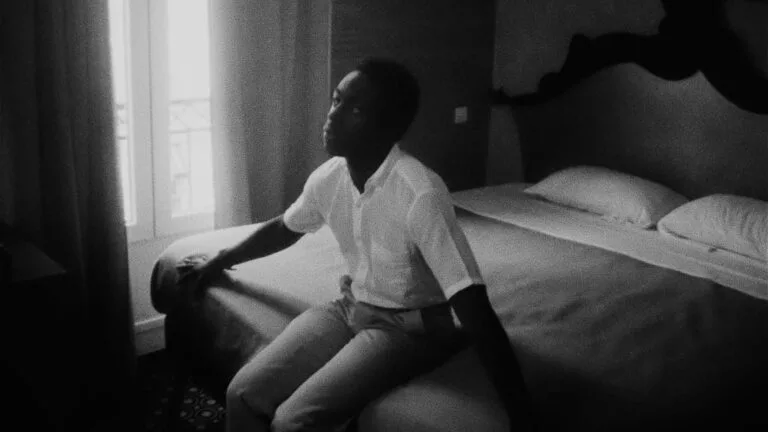

Director Yashadai Owens’ “Jimmy” On paper, it is a reimagining of author and civil rights activist James Baldwin’s early years in Paris after his departure from New York. However, in reality, this is a film that eschews traditional plot in favor of energy and mood. “Jimmy” is a “slice of life” narrative that celebrates Black boy joy through everyday moments. Shot on 16 mm film, Owens transports the audience into Baldwin’s world, giving us the sights and sounds the author would have experienced. Set design, costumes and Benny O. Through the casting of Arthur – whose resemblance to Baldwin is striking – Owens creates a compelling fantasy. Baldwin’s portrayal of Arthur is remarkably lifelike, as if Baldwin himself had leapt from his pages. He moves across the screen with effortless freedom, reflecting the sense of liberation felt by Baldwin as an immigrant disillusioned with American racism. We witness Jimmy’s inner peace as this new world opens up to him.

Owens, working as both director and cinematographer, embraces the French New Wave style, relying exclusively on natural light and shooting on location to captivate audiences. He repeatedly abandons script-driven storytelling in favor of spontaneity, capturing raw, unfiltered moments with his lens – exposure be damned. Many of the photographs fall into shadow, with unclear shapes and persistent grain, contributing to an evocative atmosphere.

His artistic choices may not appeal to mainstream audiences. As Alfred Hitchcock famously said, “Drama is life with the dull bits cut out,” and unfortunately, this film mostly feels like “dull bits.” The visual charm of mid-century Paris fades as modern technology – cell phones, cars – emerges on screen, making the setting more present day than Baldwin’s era.

While Owens’ cinematography occasionally produces stunning results, his reliance on improvisation results in inconsistencies, causing the final product to struggle to fill its runtime with only a handful of cohesive scenes. Although “Jimmy” offers a rare and insightful portrayal of Baldwin beyond America’s racism, it is ultimately not a film I would watch again.